The Ontological Argument for Gzuz

The phrase "Ontological Argument" often intimidates and confuses newcomers — atheists and Christians alike — when they first encounter it in discussions of philosophical existence, truth, and broader epistemology. But at its core, the argument is a thought experiment using pure reasoning to "prove" God's existence. Rather than relying on empirical evidence, the Ontological Argument seeks to define God into existence.

Throughout history, many philosophers — from St. Anselm to Descartes to Plantinga — have attempted to refine this argument. However, critics like Kant and Michael Lou Martin have pointed out its flaws, with Martin even using a parody to highlight its paradoxes.

In this blog, after a very watered-down coverage of what the Ontological Argument for God is and its problems, following Michael Lou Martin's use of parody to expose its contradictions, I take that same parody approach but apply it to Gzuz, a mischievous character who (conveniently) happens to fit the Ontological Argument better than the traditional concept of God. To make my case, I introduce a thought experiment: If one could construct different gods using this argument — one all-good, one all-evil, and one "just-right" — which best aligns with our reality?

A helpful Glossary for us non-philosophers

- Ontology — The study of what things are, their nature, and existence.

- Epistemology — The study of knowledge: how we know things and what counts as truth.

- A Priori — Knowledge or reasoning that is independent of experience (e.g., "All bachelors are unmarried men").

- Empiricism — The philosophical approach that knowledge is primarily derived from sensory experience (as opposed to pure reason).

- Theology — The study of the nature of God and religious belief.

- Omnipotence — The quality of being all-powerful.

- Omniscience — The quality of being all-knowing.

- Omnibenevolence — The quality of being all-too-good.

- Omnimalevolence — The quality of being all-too-bad (not a standard term but useful for this discussion).

- Theodicy — Coined by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, a philosophical and theological attempt to justify the existence of evil and suffering in a world created by an all-powerful, all-knowing, and all-too-good God.

- Cacodicy — The antithesis of Theodicy. My playful, made-up term (by me) referring to the philosophical and theological attempt to justify the existence of happinness and lack of suffering in a world created by an all-powerful, all-knowing, and all-too-bad God.

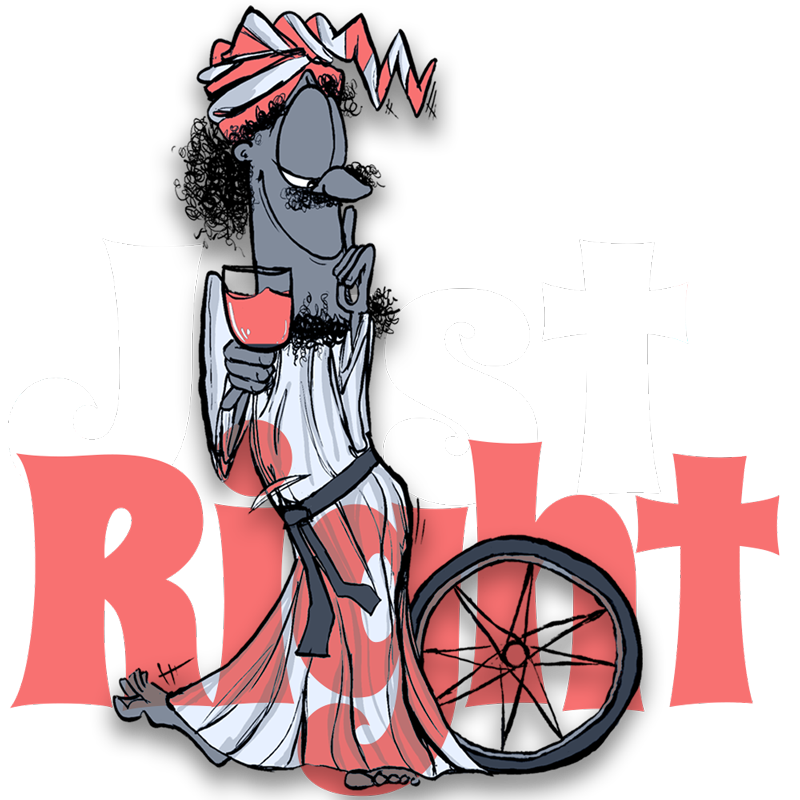

- Gzuz — The satirical, mischievous alternative to Jesus. The necessary god of "just-right." Naughty, mischievous, tipsy, and wearing a red-and-white hat to hide from his responsibilities. If you don't know him yet, dont worry — you soon will :)

NB: If it has not been made clear by me already, this blog is not an attempt to rehash the failures of the Ontological Argument for God — those fallacies have already been well documented. Rather, it is an effort to embrace them and turn them to my advantage... to prove the existence of Gzuz. Ha! What Fun!

What is the Ontological Argument for God

As mentioned before, philosophers approach ontology in a structured way to explore questions about existence. Instead of relying on scientific evidence to prove the existence of God(s), pure reasoning was historically seen as an alternative path to knowledge.

The ancient Greeks championed pure reasoning, believing that truth could be discovered through logic alone. It wasn't until skeptical David Hume and Immanuel Kant — famous for his objection based on his dictum that existence is not a predicate — came along that empiricism (the idea that knowledge must be based on experience and observation) became dominant. But before that shift, proving God's existence through rational intuition was considered a valid intellectual pursuit.

Ontology is not just about gods and metaphysics; it is the study of what things are and what defines them. For example, a business can be defined by its goals, structure, and policies; a cat by its species, behavior, and instincts; and even an object like a bag by its materials, purpose, and form. Likewise, philosophers attempt to define a god through attributes such as omnipotence and omnibenevolence, making the Ontological Argument an attempt to define God into existence.

This is where the Ontological Argument for God comes in.

In 1077, St. Anselm of Canterbury developed the Classical Ontological Argument, a purely logical (a priori) argument for God's existence. Unlike other arguments (like the Cosmological or Teleological arguments), which rely on observations about the world, Anselm's Ontological Argument tries to prove God's existence from definition alone.

Anselm's argument in Proslogion relies on the idea that God is a being that must exist by definition — his existence is self-evident once properly understood. He held that a being that exists in reality is greater than one that exists only in the mind, and since God is the greatest conceivable being, He must exist in reality.

Below is a basic construct of St. Anselm's Ontological Argument:

- P1. God is the greatest conceivable being (by definition)

- P2. It is greater to exist in reality than in the mind alone

- P3. God exists in the mind

- C1. Therefore, God exists in reality

Clever, is it not?

For further reading on this topic, consider:

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Ontological Arguments

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: St. Anselm

From Classical to Modal

Historically speaking, the Ontological Argument has two main versions: the Classical and Modal forms.

The Classical Ontological Argument for God began with St. Anselm. Over the centuries, philosophers such as Descartes sought to refine and defend it, strengthening its logical foundations. However, Immanuel Kant's (1724–1804) critique — particularly his argument that "existence is not a predicate" — dealt a significant blow to the Classical Ontological Argument, exposing its fundamental weaknesses.

In its wake, a new and more refined approach was needed — leading to the emergence of Modal Ontology.

While the Classical Ontological Argument relied on pure definition and conceptual necessity, the Modal Ontological Argument introduces a new layer — possibility and necessity, grounded in modal logic.

This shift was made possible by the work of philosopher C.I. Lewis (1883–1964), who developed S5 Modal Logic. S5 allows for a crucial inference: if something is possibly necessary, then it is necessarily actual.

Plantinga capitalized on this logical framework to reformulate the Ontological Argument in a modal form. Rather than arguing that God must exist simply by definition (as Anselm and Descartes did), Plantinga's version hinges on the claim that a Maximally Great Being — if even possible — must exist in every possible world, including our own.

In other words, Modal Ontology does not just ask, "What is the greatest conceivable being?" as Classical Ontology did. Instead, it asks, "If such a being is possible, what does necessity demand?"

The answer, according to S5 logic, is that it must exist.

In a nutshell, Plantinga's Modal Ontological Argument is as follows:

- P1. It is possible that a Maximally Great Being (God) exists.

- P2. If a Maximally Great Being exists in some possible world, then it exists in every possible world (because necessary existence is a great-making property).

- P3. If a Maximally Great Being exists in every possible world, then it exists in the actual world.

- P4. If a Maximally Great Being exists in the actual world, then it exists in reality.

- C1. Therefore, a Maximally Great Being exists.

The big problem with the Modal Ontological Argument — and I shall exploit this to its fullest extent to prove the existence of Gzuz — is it's begging the question fallacy, as pointed out by Kant. This flaw is then brilliantly exposed by Michael Lou Martin (1932–2015), an American philosopher and a former professor at Boston University. His critique, famously known as The Ontological Parody, perfectly dismantles the argument's structure. (For a deeper dive, see Martin's analysis: The Ontological Parody).

Here's the issue: by simply feeding the logical machine with the right definitions of perfection and necessity, one can conjure up the "existence" of any god of their choosing. Want a deity that embodies infinite patience and loves pineapple pizza? Done. Prefer a cosmic trickster who only grants wishes on Tuesdays because he hates Mondays? No problem.

Of course, this is a Reductio ad absurdum counter argument — because if two necessary beings exist, they create a paradox. But for the sake of satire, I propose a god who makes far more sense than traditional concepts.

Not an all-good god.

Not an all-evil god.

But rather, Gzuz — somewhere in between; slightly inebriated, necessarily existing, getting up to nonsense, hidden because of a magic hat and... well, just perfectly useless!

I suggest we delve a little deeper and conduct a thought experiment by putting all three god types into the mix to see which best reflects our reality.

The God experiment

Given the history of Modal Ontological Arguments, let's start with the Omnibenevolent, Omniscient, Omnipotent god. After all, this is the god traditionally argued for by Christian theologians.

The All-Too-Good God

If we assume that such a loving and all-powerful god exists, we immediately run into theodicy — a fancy word meaning God's Justice. Well... where is it?

This term exists because reality demands it. How do we explain suffering? Theodicy attempts to justify the apparent contradiction between an all-good, all-powerful god and the observable reality of suffering and evil.

A god who watches indifferently as innocent children are raped?

A god who allows cancer, earthquakes, and natural disasters to kill millions at random?

A god under whose rule millions of children die from starvation every year?

Is he loving but not powerful? Or powerful but not loving?

As Epicurus (341–270 BCE) famously put it:

"Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is not omnipotent.

Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent."

Clearly, omnibenevolence does not hold up.

The All-Too-Bad God

What if we flip the script? What if God is Omnimalevolent — Omniscient and Omnipotent, but completely evil?

This fails just as miserably.

In the same way, under the reign of an all-evil god, we would be left wondering why puppies are so cute, why the theme of love is so popular in music, and how it is conceivable that one can be amazed and emotionally moved by the beauty of a sunset — or moonrise, for that matter."

If an all-evil god ruled, we would need a new branch of philosophy — perhaps "Cacodicy" (from kakos, Greek for “bad” + dike, meaning “justifying badness”)?

But, just like the omnibenevolent god, this god does not match reality.

The Just-Right God?

What about something in between?

Not omnibenevolent.

Not omnimalevolent.

But rather... Omniambitrickivalent.

Yes, I made this word up. But it fits.

- ✓ Perfectly mischievous

- ✓ Perfectly morally ambivalent

- ✓ Perfectly absentminded

- ✓ Perfectly hidden

Now this aligns with reality!

We see a world with both good and bad.

A world of opportunity and suffering, joy and absurdity.

A world where the god seems distracted... or maybe just a bit tipsy.

Therefore, Gzuz

Introducing Gzuz — a god who perfectly matches the world we observe and live in.

A god with a curious love for wheels, distracted by a magic hat, and a never-ending glass of red wine.

And, for sh%ts and giggles, let's prove his existence using the Modal Ontological Argument:

- P1. It is possible that Gzuz exists.

- P2. If Gzuz exists in some possible world, then Gzuz exists in every possible world (because necessary existence is a great-making property).

- P3. If Gzuz exists in every possible world, then Gzuz exists in the actual world.

- P4. If Gzuz exists in the actual world, then Gzuz exists in reality.

- C1. Therefore, Gzuz exists.

Gzuz. Love him or hate him, but you can't argue — he is Perfectly Necessary.

So, raise a glass of red, and maybe a red-and-white striped hat too... Cheers!